UPDATED 19 MARCH 2020:

In January, risk #1 described how US institutions would be tested as never before, and how the November election would produce a result many would see as illegitimate. If President Donald Trump won amid credible charges of irregularities, the results would be contested. If he lost, particularly if the vote was close, same. Either scenario would create months of lawsuits and a political vacuum, but unlike the contested George W. Bush-Al Gore election of 2000, the loser was unlikely to accept a court-decided outcome as legitimate. It was a US version of Brexit, where the issue wasn't the outcome but political uncertainty about what people had voted for.

The coronavirus outbreak heightens these risks and brings them forward. Georgia, Louisiana, Kentucky, and Ohio are the first states to delay their primaries due to coronavirus fears, and they surely won't be the last. Many voters won't feel safe casting a ballot in person, a fear that will be amplified by misinformation.

As the administration's handling of the coronavirus outbreak continues to attract criticism, and the economy tumbles into recession, Trump will be tempted to sow doubts about the integrity of the election, not to mention aggressively going after presumptive Democratic nominee Joe Biden and his son Hunter. Health fears and rumors about the likely Democratic nominee are already being weaponized for political ends, and politicized investigations are likely. Meanwhile class tensions will be exacerbated, with many blue-collar workers unable to easily work from home, school cancelations wreaking havoc on poor and single-parent families, and possible violence and disruptions over access to both public and private medical care. Already, generational divides are sharpening, with many young Americans, at lower risk of dying from the coronavirus, defying orders for “social distancing.” The run-up to this election will be the most divisive in modern history.

As the campaign season progresses, a candidate trailing in the polls could play on social anxiety to call for a delay in the vote—even if the date is legally very difficult to change because it would require legislation that could win approval from Congress, the president, and the courts. More likely, states could shift most voting from in person to absentee paper and/or online ballots. This approach would bring new risks. There is currently no plan B for an election that can't have people voting at polls. If states turn to the mail, can it be done securely, will it structurally favor one side, and will that tempt one or both candidates to undermine its credibility? If the US goes to e-voting, nefarious actors will see greater opportunity to disrupt the process. Even without malign interference, all it would take is a technical glitch to call the results into question. Who would it help? No one knows, which is exactly our point.

After the election, the vote could be contested on grounds of tampering, procedural flaws, and/or historically low turnout. Whoever wins would lack full authority in the eyes of Americans and the international community. The US Congress could become even more dysfunctional than we expected in January, not least because of teething pains as it learns to work remotely—all amid a crisis over the vote. Finally, on foreign policy, the coronavirus will cause the US to turn inward and increase its isolation from the world. Less US leadership and reassurance to allies will be the result.

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED 6 JANUARY 2020:

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED 6 JANUARY 2020:

WE'VE NEVER LISTED US DOMESTIC POLITICS AS THE TOP RISK, mainly because US institutions are among the world's strongest and most resilient. This year, those institutions will be tested in unprecedented ways. We face risks of a US election that many will view as illegitimate, uncertainty in its aftermath, and a foreign policy environment made less stable by the resulting vacuum.

Institutional constraints have prevented President Donald Trump from realizing major parts of his agenda (much as they have presidents preceding him), but they haven't stopped him from dividing the nation. Can a country this polarized move forward? Trump has been impeached in the House of Representatives, and he will be acquitted by the Senate. This dynamic will delegitimize the November presidential election. Democrats will feel impeachment was politically quashed to place the president above the law, while Trump will feel empowered to interfere with election outcomes, with impeachment no longer a credible instrument of political restraint. At the same time, there will be external interference in US elections, especially from Russia, and the president and the Senate will do little to minimize the damage via tighter election security measures.

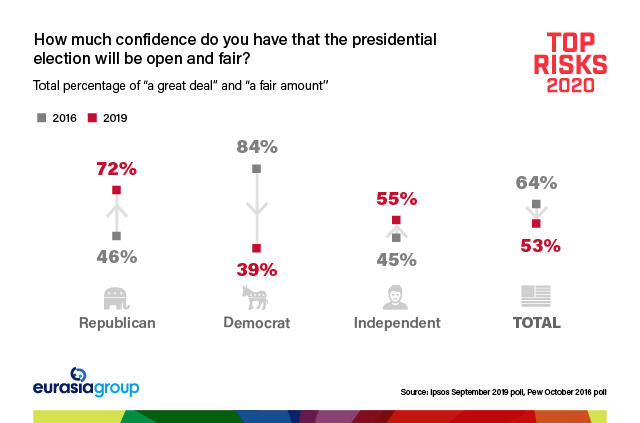

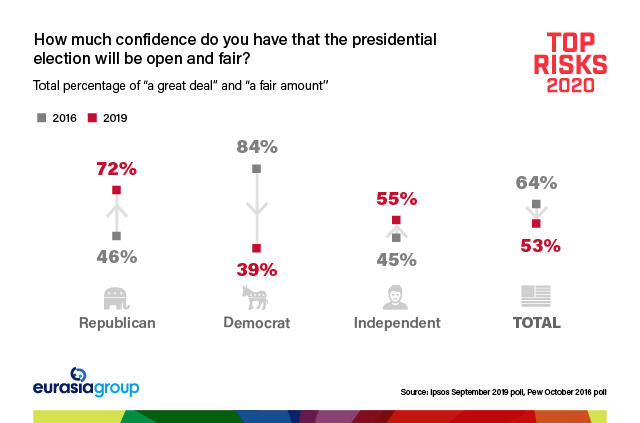

In other words, we'll have an election that—in advance—will be perceived as “rigged” by a large percentage of the population. Public opinion polls already show this risk is on the rise. According to a 2019 poll by IPSOS, just 53% of the public believed the presidential election will be fair. But the biggest drop in confidence has come among Democratic voters. In 2016, 84% of Democrats believed that year's election was fair; the number fell to 39% in September 2019 when asked about this year's election.

Legal challenges, which will likely fail in a conservative-leaning Supreme Court, could even lead to calls from some quarters for the vote to be postponed or boycotted, which would be unsuccessful but further undermine electoral legitimacy. Alternately, if Trump feels he's likely to lose, he could blame external actors such as Ukraine for interference and attempt to manipulate outcomes (especially in existing but vulnerable red states, where Trump allies hold political sway) in the name of ensuring election security. It will be the worst political climate for a national election that the US has experienced since the (effectively failed) election of 1876.

What happens then? If Trump wins amid credible charges of irregularities, the election process will become contested. If he loses, same. Particularly if the vote is close, and it's likely to be. That would lead to lawsuits reminiscent of the Al Gore-George W. Bush election in 2000 that was ultimately decided in the Supreme Court. But unlike Gore-Bush, it's hard to see a scenario in which the high court rules and the loser graciously accepts the outcome as legitimate, especially if the loser is Trump. In other words, the 2020 election is an American Brexit—a maximally polarized vote where the risk is less the outcome than the political uncertainty of what the people voted for. It's uncharted political territory, and this time in a country where uncertainty creates shockwaves abroad.

Meaningful (France-style) social discontent becomes more likely in that environment, as does domestic, politically inspired violence. Also, a non-functioning Congress, with both sides using their positions to maximize political pressure on the eventual election outcome, setting aside the legislative agenda. That becomes a bigger problem if the US is entering an economic downturn, on the back of expanded spending and other measures to juice the economy in the run-up to the election.

The challenge extends to foreign policy as well, because any decisions Trump makes on security or trade questions in that environment would be viewed as lacking authority. Enemies will see the US presidency as the weakest it's been since Richard Nixon was embroiled in Watergate, and this time, there's no Henry Kissinger. Reckless pursuit of diplomacy is safer than reckless pursuit of war—Trump's preference is to “pet the dog” rather than “wag it” (making bad deals with foreign governments rather than launching attacks on them)—but that still means unprecedented efforts by Trump to align US policy with the interests of antagonists and frenemies such as Russia and Turkey. Meanwhile, with allies and partners, Trump's policies coupled with turmoil in Washington will confuse and further destabilize longstanding relationships, with big question marks over countries that already feel particularly exposed: think South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and Saudi Arabia. And Trump is also more inclined to miscalculate (and increasingly unconstrained by advisers when he does so), making tail risks around those geopolitical confrontations that occur more unpredictable (see Iran) … and dangerous.

More broadly, both US allies and enemies over the past years have come to wonder whether the United States intends to lead—and they've hedged their bets accordingly. In the midst of a disputed 2020 election, many of those countries will wonder whether the US can govern itself. It's a period of unusual geopolitical vulnerability to shock and escalation.

To be clear, we're not worried about the long-term durability of US political institutions. The United States doesn't face the danger of losing its democracy in 2020. Nor are we as alarmed as the markets about a “lurch to the left” in US policy—a Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren presidency remains plausible but unlikely; and more importantly, the next president will face the same congressional and other institutional constraints Trump has (though please see

risk #4 on the broader pushback against multinationals). But a broken impeachment mechanism, questions of electoral illegitimacy, and a series of court challenges will make this the most volatile year of politics the US has experienced in generations.