Xi emerged from China's 20th Party Congress in October 2022 with a grip on power unrivaled since Mao Zedong.

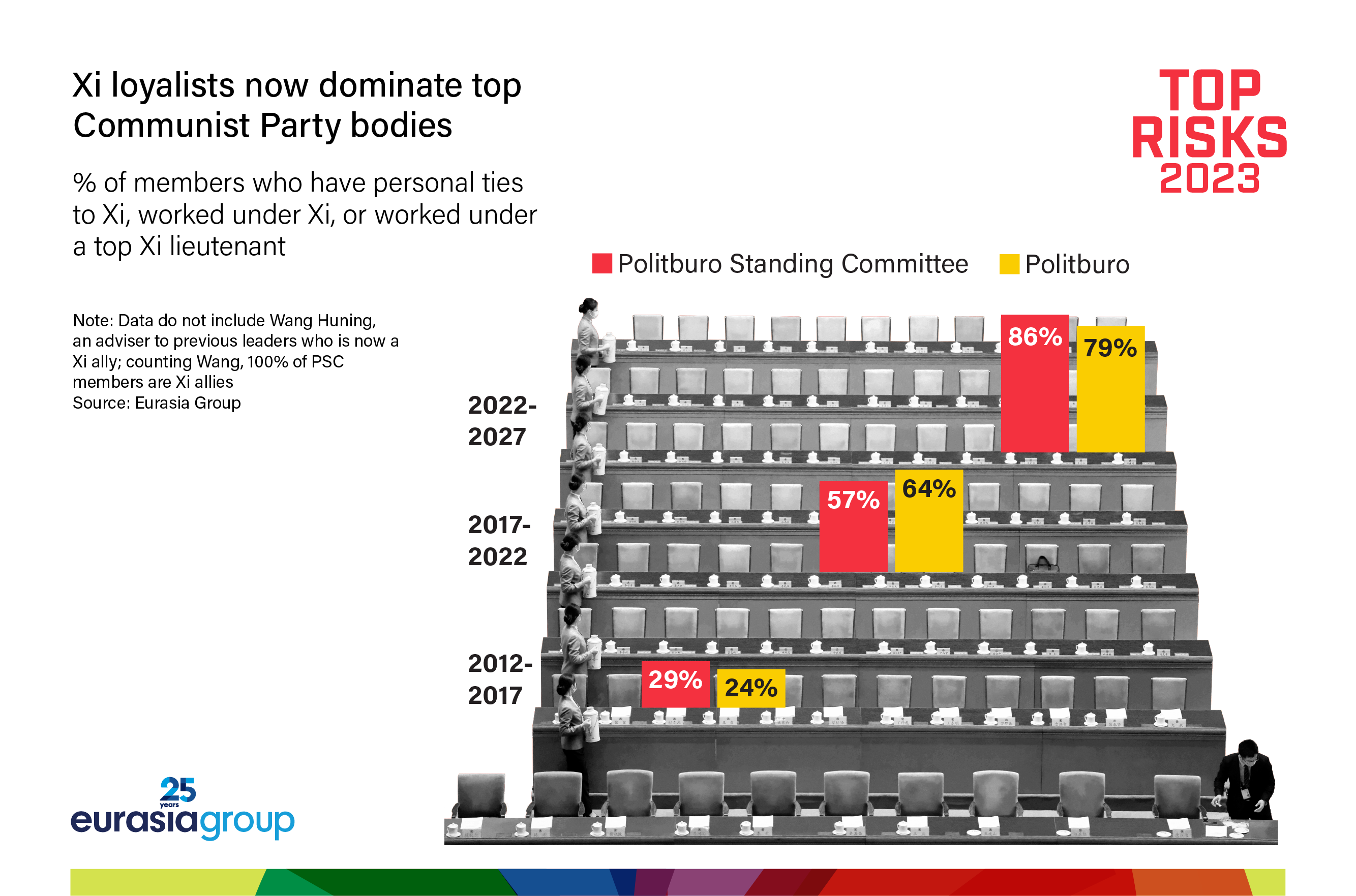

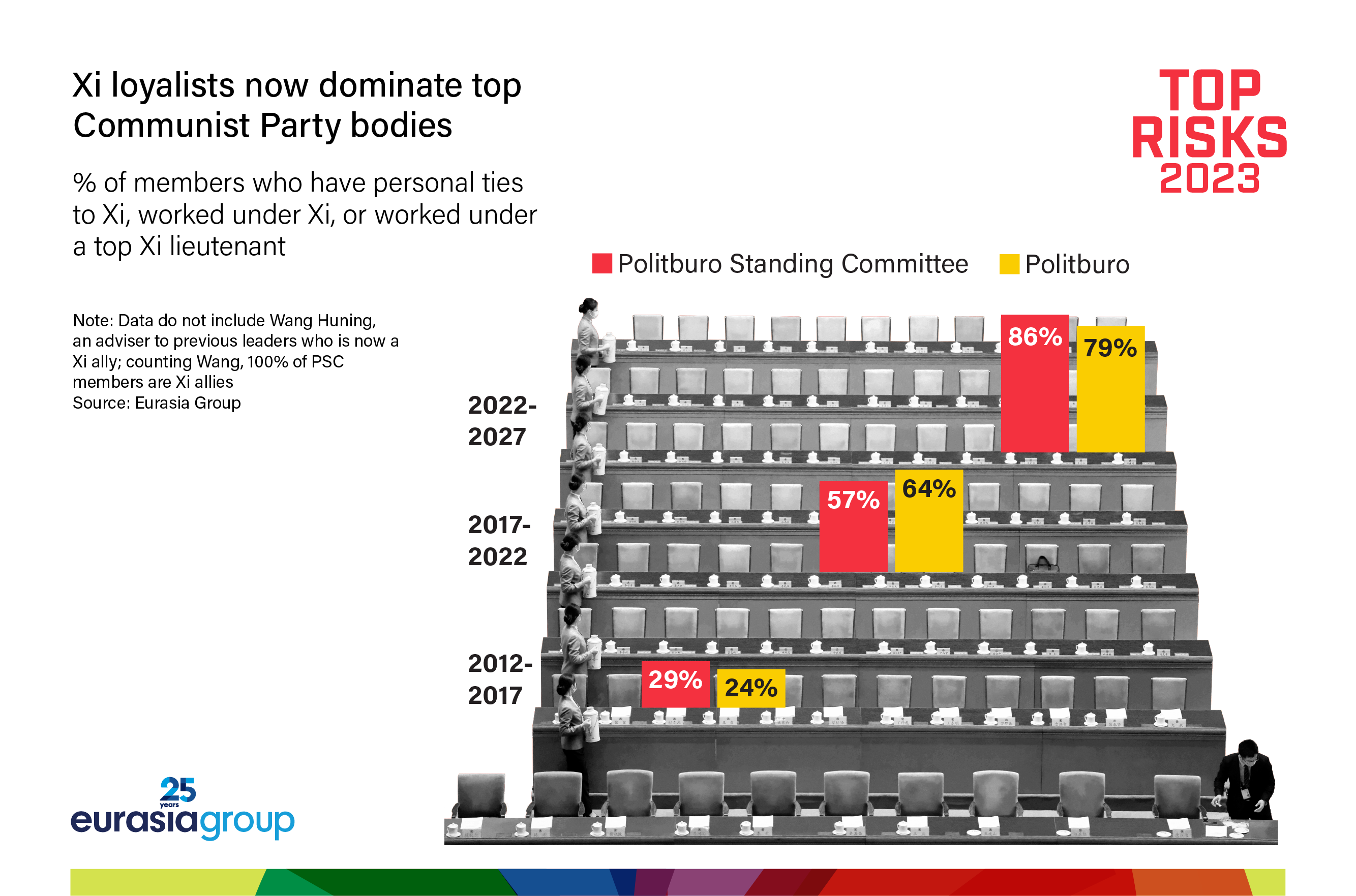

Having stacked the Communist Party's Politburo Standing Committee with his closest allies, Xi is virtually unfettered in his ability to pursue his statist and nationalist policy agenda. But with few checks and balances left to constrain him and no dissenting voices to challenge his views, Xi's ability to make big mistakes is also unrivaled. Arbitrary decisions, policy volatility, and elevated uncertainty will be endemic in Xi's China. That's a massive and underappreciated global challenge, given the unprecedented reality of a state capitalist dictatorship having such an outsized role in the global economy.

Xi has committed a series of missteps in the recent past.

Last year we warned that China had walked itself into a zero-Covid trap; unfortunately, we were right. Xi's refusal to offer high-quality, foreign-made mRNA vaccines, combined with underwhelming vaccination drives even with locally made doses, left the Chinese population more vulnerable to severe disease than it should be, and have made Xi's sudden and surprise exit from zero Covid much deadlier.

An opaque crackdown on private technology companies undercut global investor sentiment, put some of the country's most promising firms into a deep freeze, and wiped out an estimated one trillion dollars in market value.

And Xi's announcement of a “no limits friendship” with Russia on 4 February 2022 lent credibility to Putin's war in Ukraine and darkened perceptions of China's influence on the global system.

In each instance, Xi's authoritarian personality and policy preferences—political control, economic statism, and assertive diplomacy—overrode the advice of pragmatic voices within the bureaucracy. And that was before Xi cemented his position as modern-day emperor. Now that all Chinese policy flows directly from a single all-powerful leader, there's even less transparency on the decision-making process, less information flowing to the top, and less room to admit error, course correct, or compromise.

We see risks in three areas this year, all stemming from Maximum Xi.

First, the ill effects of centralized decision-making on public health are now on display. Just weeks ago, Xi ended the zero-Covid policy in the same arbitrary manner that he implemented it more than two years ago. His snap decision to lift all restrictions and let the virus spread unchecked despite low elderly vaccination rates, without warning citizens and local governments, and absent sufficient preparations to cope with the resulting outbreaks will all but ensure that more than one million Chinese people will die, many unnecessarily (though most will not be reported). Only a leader with unchallenged power could execute such an extraordinary—and extraordinarily costly—reversal.

Moreover, if a severe new strain of Covid were to emerge, Maximum Xi makes it more likely that it would spread widely in China and beyond. China would be unlikely to identify the new variant because of reduced testing and sequencing, to recognize more severe disease due to an overwhelmed health system, and to let news of a more severe variant get out given Xi's track record on transparency. The world would have little or no time to prepare for a deadlier virus.

A second area of concern is the economy, where Xi's drive for state control will produce arbitrary decisions and policy volatility. China's economy is in a fragile state after two years of harsh Covid-19 controls. Forced deleveraging efforts and plummeting homebuyer and market sentiment have ground growth in the critical real estate sector to a halt, depleting local government revenue. Debt defaults threaten to spread to the broader financial sector. It has long been the case that more global GDP growth was coming from a politically riskier market as China's economic footprint expanded. But in 2023, China's outlook is even more important, given the rising risks of recession elsewhere (please see risk #4).

This backdrop—of weakening global growth and deepening domestic challenges—demands competent economic management from Beijing. But the Chinese leadership is delivering opacity and unpredictability. China's sudden decision to delay the release of long-scheduled economic data during the 20th Party Congress was an ominous sign of things to come for global markets. At a minimum, heightened market and company sensitivity to the singular voice of Xi will invite volatility in response to any signals he conveys, resulting in a repricing of credit risks that in turn drives debt defaults and bankruptcies. Beijing will struggle to manage these pressures in an environment of centralized power and stifled debate.

A final risk area is foreign policy, where Xi's nationalist views and assertive style will drive Beijing's relations with the world. Xi isn't looking for a near-term crisis, given the scale and immediacy of economic challenges at home. But “wolf warrior” diplomacy will nonetheless intensify as diplomats channel Xi's bold rhetoric, often at the expense of effective engagement. Xi's personal affinity for Putin will limit how closely China is willing to align with the developed world—and even, in the worst-case scenarios, with developing countries—in response to increasingly rogue behavior by Russia (please see risk #1) that threatens global peace and stability. An indifferent response to Russian aggression could invite a global backlash, undermining China's international standing and adding to economic risks. China's foreign policymaking would be less marked by overzealousness and miscues if it was informed by effective debate and feedback on likely global responses. In this, as in other critical policy areas, Xi will be listening to no one more than himself.

The last time a Chinese leader had this much power to pursue such a misguided policy agenda, the result was widespread famine, economic ruin, and death. While another Cultural Revolution or Great Leap Forward is unlikely given the size of China's educated urban middle class, Xi's consolidation of power will take China at least a few steps backward this year.