The United States is no longer interested in playing the role of global policeman. Beijing is not about to take Washington's place.

No matter how many times Biden says that “America is back,” retrenchment remains the bipartisan consensus in Washington. To the extent that Washington is looking abroad, it's focused mainly on countering China's rise. Beijing will spend 2022 focused on mounting challenges at home as Xi works to secure a third term at the 20th Party Congress, contain Covid-19, and redirect the priorities of the private sector (please see

Risk #4). Xi wants to ensure his power expands, but Covid-19 doesn't—and that leaves little room for foreign policy adventures.

Other powers with interests in global stability, such as the EU, the UK, and Japan, will exercise more influence without fully filling the global power vacuum. Many countries and regions will suffer the consequences.

No one will fill the global power vacuum; many countries and regions will suffer the consequences.

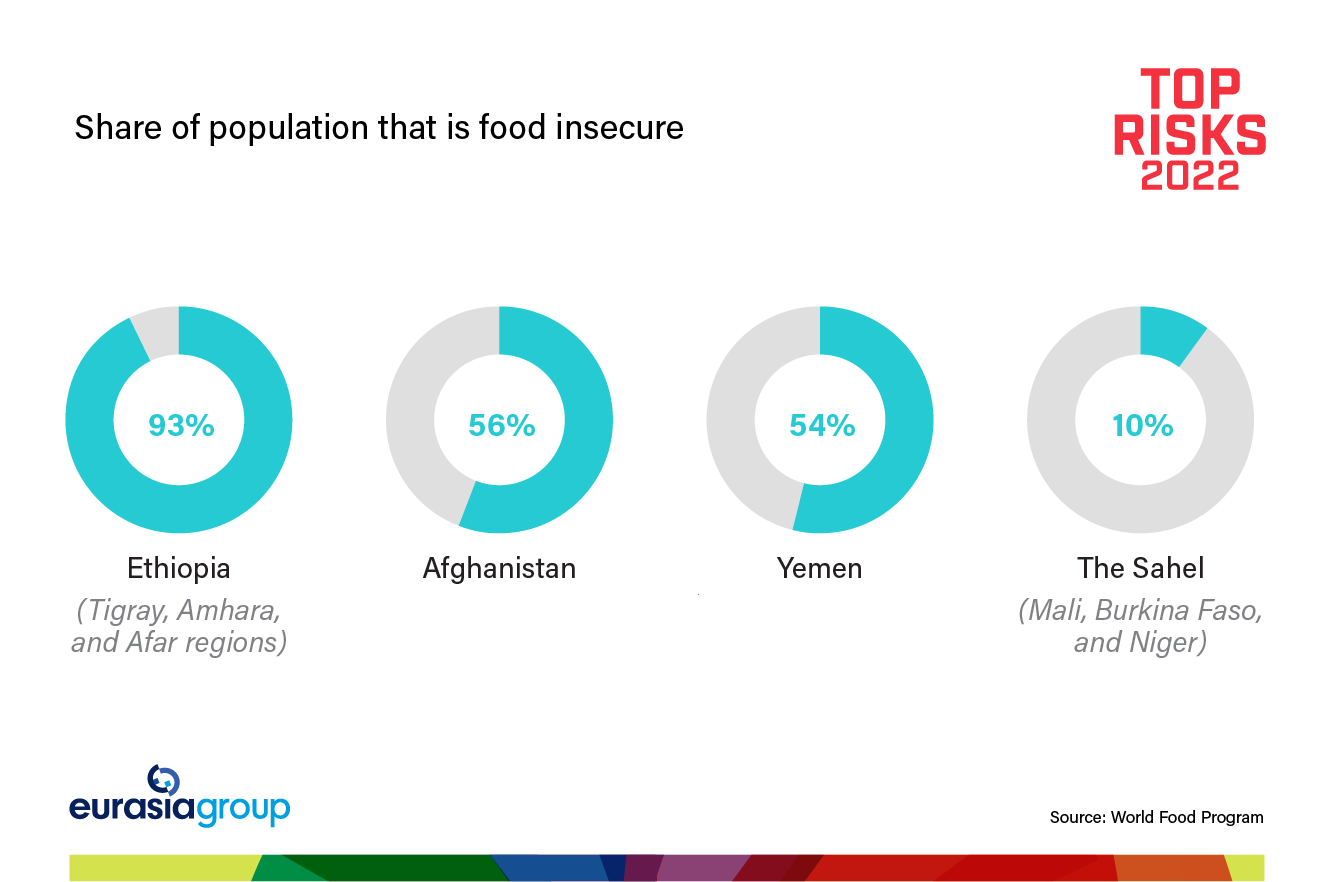

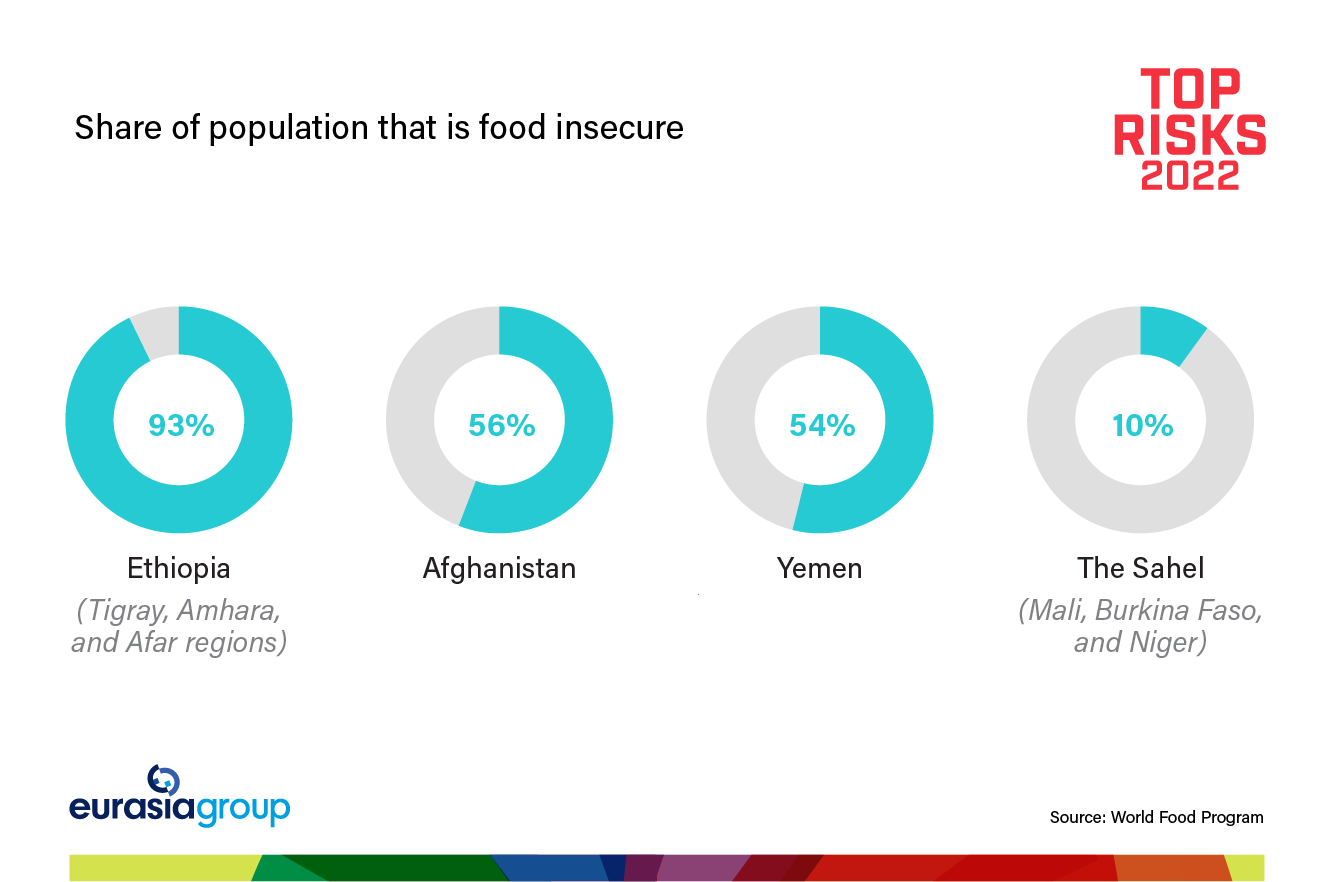

Afghanistan is the most obvious example. The collapse of its government last summer and the chaotic withdrawal of US forces left Afghanistan in the hands of an extremist, disorganized, and inexperienced Taliban force. The Taliban do not exert control over much of Afghanistan. They will struggle to stop the local Islamic State affiliate from drawing in militants from other parts of the world to settle in ungoverned expanses of the country. The US has sharply limited intent or capacity to intervene, and China has shown little interest. Afghanistan is returning to its pre-9/11 position as a global magnet for international terrorism.

The risks of terrorism are also acute in the thinly governed

Sahel. The conflict with Islamist militants has spread from Mali across the region, resulting in large-scale terror attacks in Burkina Faso, Niger, Mali, and Chad. But France is scaling back its military presence, and the US has stepped back since 2017 when four soldiers were killed in Niger. The escalation of the insurgency would have broader implications for political stability and provide another space for terrorist organizations to regroup and plot attacks on the West.

The seven-year war between a Saudi-led coalition and Iran-backed Houthi rebels in

Yemen presents similar risks. After scaling back military support for Riyadh, the United States has done little to push for a cease-fire or to ease suffering. The effects will extend beyond Yemen. Houthi attacks damage oil facilities critical to the global economy in Saudi Arabia and increase regional tensions with Iran. Counter-terrorism efforts will continue to falter, giving breathing room to the capable Al Qaeda affiliate there.

Both

Myanmar and

Ethiopia are in the throes of civil conflict. In Myanmar, the ruling junta cannot fully contain a civil disobedience movement and resistance from armed ethnic minority organizations. The United States has treated Myanmar as a low-priority issue, and while China supports the junta, it has done little to push for a resolution. The main risk for outsiders will come from refugee flows, especially to India and China, which are both trying to keep fleeing civilians out. Some of the same dynamics are present in Ethiopia. More than a year into the civil war, military momentum continues to swing between government and antigovernment forces with devasting results. The US approach has been incoherent, while China has given the government some diplomatic cover and arms. The conflict, which shows no immediate signs of stopping, risks destabilizing the Horn of Africa and increasing refugee flows.

Likewise, the bleak situations in

Venezuela and

Haiti also risk refugee flows in North and South America. The political and economic crisis in Venezuela has already spurred millions to leave, and the US has put little effort into improving the frozen situation. Haiti is mired in political instability, which has already caused thousands of Haitians to flee to the US southern border.

During the Cold War, thinly governed spaces across Asia and Africa became battlegrounds for proxy conflicts between Washington and Moscow. The competition was global and zero sum. That's not the case anymore—the United States and China are content to let some places languish. It's another clear sign that we're not in a Cold War 2.0 (please see related

Red Herring).