The

UK granted emergency use authorization to Pfizer-BioNTech's Covid-19 vaccine last week, a critical turning point in the world's fight against the pandemic. But while the start of vaccine rollout is great news, it's also complicated … Here's why.

Why it matters:

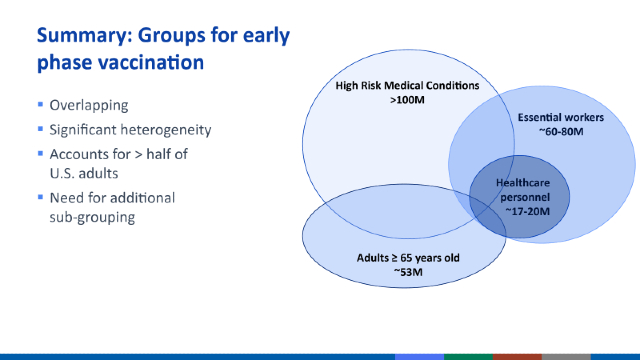

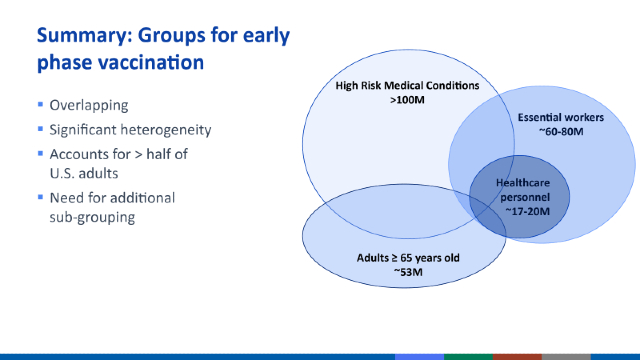

Who gets first access to a limited supply of vaccines was always going to be controversial, at both the domestic and international levels. Let's start with the domestic; for the world's advanced industrial democracies who are leading the pack in vaccine development, the first run of vaccines will be earmarked for frontline workers and nursing home residents. Operation Warp Speed has effectively commandeered the

US vaccine supply for about the next eight months; even that isn't without debate as questions have been raised about whether vaccinating the elderly in homes is really the best use of a limited vaccine supply. After the first wave of vaccines is distributed, it then goes to “essential workers,” a not easily defined term that varies from context to context. In the US, states will be the ones to make distribution decisions and define who qualifies as “essential," which means we are looking at potential political fights across all 50 states. But even in more centralized federal systems, the same challenges of defining categories of workers and which ones to prioritize remains daunting.

This is

the best graphic I've come across that captures the current situation:

Credit: Katherine Dooling

Credit: Katherine Dooling

The good news for advanced industrial democracies leading the vaccine race at moment is that it won't matter if you're insured or not; the bad news is that even if the government pays for it, a substantial amount of people still won't want to take it. Some of that is coming from folks with longstanding vaccine skepticism, some from folks who just don't feel comfortable with the breakneck speed and the seeming politics played with developing these vaccines. Then there are the long-term concerns of inequality once the initial-distribution phase ends, with the potential of quicker uptake among urban and wealthier vs. rural and poorer citizens, further widening divides Covid-19 has

already wrought on the labor market. And as history has shown, widening economic divides lead to widening political divides.

Still, given the alternative—not having a vaccine to distribute at all—these are good problems to have. It's just that not all countries are privileged enough to have these problems. Which brings us to the developing world.

What happens next:

Developing countries are likely to be excluded in the first wave of high-caliber vaccines being rolled out at the moment by the likes of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna. There will be some goodwill gestures by expanding some limited form of access to them, but the societies able to materially improve their situation and economies on the back of the vaccine the quickest will be the advanced industrial democracies and those developing countries with significant vaccine manufacturing capabilities (think China, Russia, Brazil, Mexico, India, and Indonesia) … exacerbating global inequality between countries, not just within them.

The WHO-backed COVAX initiative remains the de facto way to distribute vaccines equitably across the world. But major countries haven't signed on (most notably the US), and even those that have are also pursuing separate deals that likely supersede their COVAX commitments. There is hope that Joe Biden will provide a major boost to coordinating vaccine efforts, but at this point in the vaccine development race, we are still looking at more vaccine nationalism than vaccine cooperation.

As of this writing, the US, UK, EU, Russia, and China all look to have some access to vaccines over the course of the next month or two. Each were able to gain priority access through either purchase, development, or production agreements of specific vaccines. When it comes to BioNtech-Pfizer vaccine, the US, Germany, and China are first. For the Moderna vaccine, the early batches will go to the US and Switzerland, the latter will support the manufacturing process for the vaccine. China's CanSino and other vaccine efforts will be targeted to the Chinese market, but given that lots of Chinese seemingly prefer to wait for a higher-quality US or European vaccine (it doesn't help that China is pushing out vaccines before phase III trials are finished), China's vaccine effort will likely be used for the developing world and to boost China's vaccine diplomacy efforts. Russia's Gamaleya Institute vaccine—the one whose effectiveness

seemingly rises with each new round of data released by competing Western vaccines—will be intended for Russians and citizens of countries in Russia's orbit, but unlikely to get much traction in the US/Europe.

There are a number of other vaccines in the works as well, but one in particular deserves more attention. In recent weeks, the vaccine being developed by AstraZeneca and Oxford University has received much news coverage. The EU, India, Brazil, and Russia are the ones that stand to benefit first if and when the AstraZeneca vaccine gets rolled out. But here's the thing:

the initial AztraZeneca data released has some serious issues (dosing errors, full clinical protocols still unpublished, a smaller sample size compared to competitors, etc. …) that raises worries about whether its effectiveness is anywhere near the

90%+ announced by Moderna and BioNTech-Pfizer. More trials are underway, which will bring more clarity over the next couple months, but if it's shown to be less effective than other vaccines being currently rolled out, that's going to result in it being more of a solution for the developing world than the developed world.

That's a particular problem for Europe, because it has far more invested in the AstraZeneca vaccine and the underlying technology that powers it. Moderna's vaccine is the US's ticket out of this crisis. And until the US exhausts its demand for the Moderna vaccine, others will have to wait (Switzerland excluded, since they are manufacturing some of the doses). And there are countless other variations and trade-offs of this sort as the vaccination effort begins in earnest.

As a world, we've now shifted from racing to find a vaccine to racing to make sure there are enough of them so that the distribution process doesn't tear us apart. In 2020, that still qualifies as exceedingly good news.

The key statistic that explains it:

“Most of this [manufacturing] capacity [for the leading vaccine candidates] is already spoken for. The 27 member states of the European Union together with five other rich countries have pre-ordered about half of it (including options, written into their contracts, to order extra doses, and negotiations that have been disclosed but not yet finalized).

These countries account for only around 13% of the global population.”

The key quote that sums it up:

“'Suppose the US marches ahead and gets a lot of its population vaccinated faster than in Europe, you can imagine the pressure European politicians are going to come under,'

said Simon Evenett, a professor of international trade and economic development at the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland. 'As a source of tensions between countries, this really could spiral.'”

And not just between the US and Europe, either.

The one thing to read about it:

Be sure to check out

the latest white paper from Eurasia Group (commissioned by the Gates Foundation) on why an equitable vaccine distribution, rather than a race to the finish line, is the better path for the world. By a lot.

The one major misconception about it:

Less a misconception, and more a critical unknown—vaccines have shown themselves able to prevent individuals vaccinated from contracting the disease,

but can they still spread it to others who haven't been vaccinated? We're about to find out.

The one thing to say about it on a Zoom call:

The best news is that we will see mortality rates come down even further between now and spring/summer 2021 as society's most vulnerable are afforded newfound protections for a disease that didn't exist a year ago. That's an extraordinary testament to how far science has come; politics is another matter.

The one thing to avoid saying about it on a Zoom call:

You could mention that the world has never before tried to roll out anything as complex or ambitious as this Covid-19 vaccination campaign, and a lot can still go wrong. Or, that the importance of this rollout has now made Covid vaccines an even greater target for shady actors like

hackers and the

mafia. But I'd hold off. We haven't had much to celebrate in 2020, so let's try not to ruin the moment.

This article originally appeared in TIME Online. Learn more:

Image courtesy of REUTERS.

Image courtesy of REUTERS.