China's currency has proved itself

A prudent approach to the coronavirus crisis from the PBoC

As the coronavirus crisis has rippled through the world economy and financial markets, many central banks, in both advanced economies and emerging markets, have taken extraordinary measures to cushion the financial sector and maintain global liquidity. The People's Bank of China (PBoC) has been no exception. But, the PBoC has also applied a degree of restraint, in rhetoric at least, which is notable. For instance, the seven-day reverse repo rate, China's key short-term interest rate, was only 30bps lower in July than where it started the year.

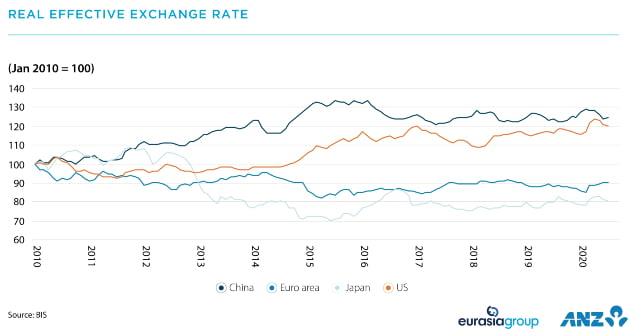

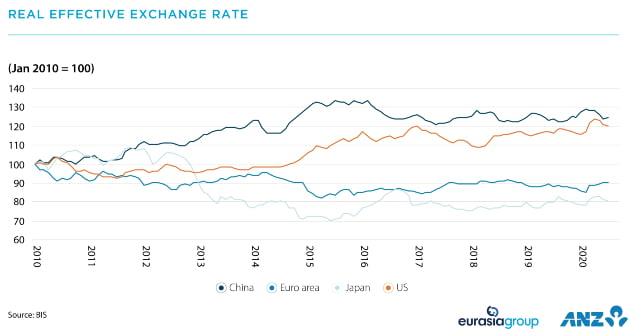

The PBoC has eschewed radical policy measures, such as large-scale quantitative easing purchases, and Chinese authorities have maintained the more flexible approach to exchange rate policy adopted since the '811' reforms of 2015. While the CNY real effective exchange rate has undergone a substantial adjustment over the last decade, since 2016, it has remained broadly stable in comparison to other major currencies, and is not substantially misaligned.

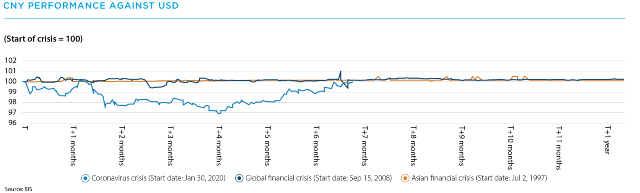

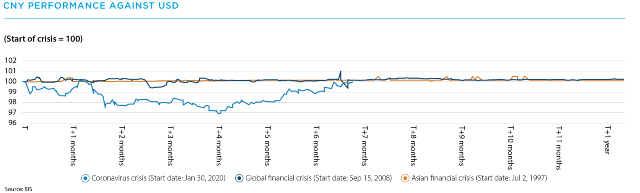

For the third global crisis in a row, the CNY has remained broadly stable

For the third global crisis in a row, the CNY has remained broadly stable

Since the onset of Covid-19, the same has been broadly true of the CNY in nominal terms. This occurred despite concerns from some observers that Chinese authorities might consider allowing a sharper depreciation, especially given the drag exerted on the Chinese external sector by higher US tariffs. Instead, the CNY has not moved significantly against the USD, even though it has remained flexible. This is a striking contrast to the global financial crisis when financial volatility drove the PBoC to effectively peg the CNY to the dollar to shield the Chinese economy.

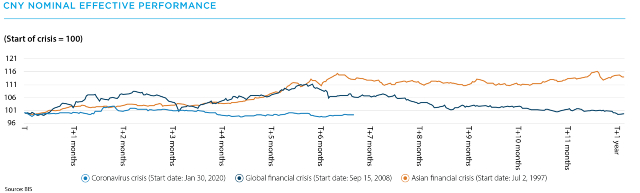

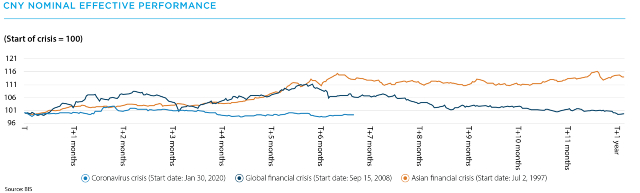

On a nominal effective basis, the CNY has also been quite steady in 2020 despite the events of the year. Part of this steadiness is by design; the authorities track a basket of currencies in setting the exchange rate and have made other recent innovations, such as incorporating a counter-cyclical adjustment factor into the country's currency policy. More fundamentally, however, these developments are growing evidence of the CNY's maturity.

Multiple factors militate against CNY depreciation

Multiple factors militate against CNY depreciation

In some respects, China's currency policy should be unsurprising. A sharp depreciation would do little to aid the broader strategic objective for internationalisation of the CNY, which reached a milestone with its inclusion in the IMF's SDR basket in October 2016. There is some risk it might be misread by other countries, or even cause broader financial distress in the country's financial sector. There were some suggestions of this in 2015–16, following the August 2015 depreciation. To the extent this was the first sizeable depreciation of the CNY, identifying some systemic adjustment would seem reasonable.

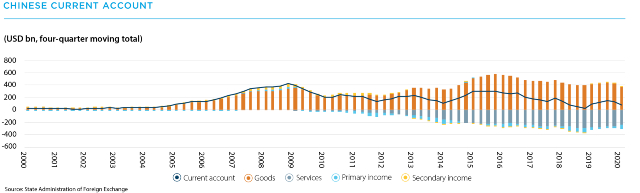

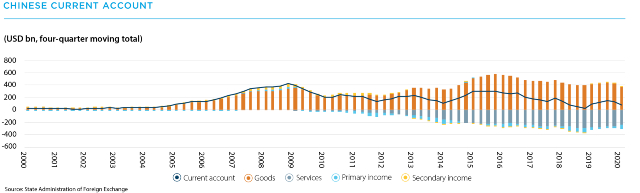

The CNY also benefits from several structural factors that limit the prospect of an abrupt depreciation. Although the current account has rebalanced considerably in recent years, the Chinese economy continues to run a sizeable trade surplus, which helps to underpin the CNY.

The trade surplus has been coupled with strong foreign demand for Chinese equities and bonds. In addition to ongoing investor demand, the inclusion of Chinese government bonds in the Bloomberg Barclay's Global Aggregate Index, which will be fully phased-in by November 2020, could lead to a total of USD 150bn in new investment inflows. While the turmoil triggered by Covid-19 may delay the trend toward indexation, demand for Chinese financial assets is expected to remain firm over the medium term, particularly given China's faster recovery from the pandemic than any other major markets.

Official data suggest pressures on the CNY are manageable

Official data suggest pressures on the CNY are manageable

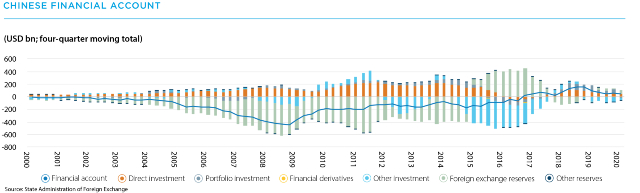

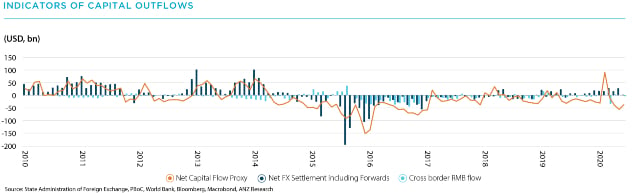

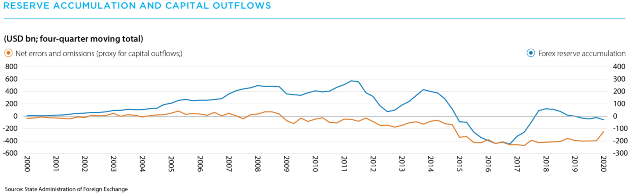

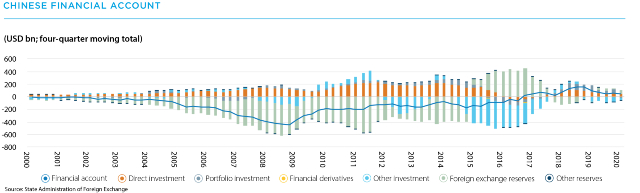

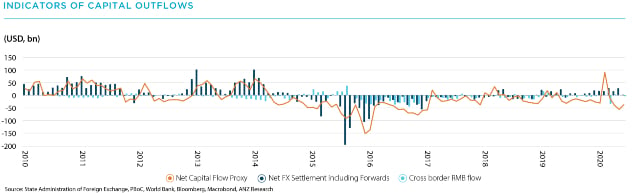

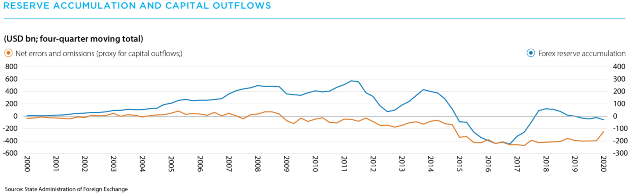

Despite the shock to the real economy posed by Covid-19, China does not appear to be suffering from large-scale capital outflows either. On a four-quarter moving total basis, the official balance of payments data show that the country has run a surplus on the financial account—indicating net borrowing, or capital inflows from the rest of the world—since 2017, when outflow pressures slowed as administrative controls on the currency were tightened. In the first quarter of 2020, when China was in the midst of its own Covid-19 response, the economy still recorded a financial-account surplus of USD 11.2bn. Net FDI inflows remained positive, at USD 16.3bn, as did other investments, at USD 27.7bn. Although China did record net portfolio and derivative outflows (of USD 53.2bn and USD 4.6bn, respectively), these were more than made up for by a modest USD 25.1bn decrease in reserves. Preliminary second-quarter data also suggest that reserves grew by about USD 19bn in April-June, largely offsetting the first-quarter fall.

Meanwhile, the errors and omissions term in the balance of payments, which is viewed as an indicator of concealed capital flight, has corrected sharply over the last year, even turning positive in the first quarter of 2020. It is possible that this was due in part to the shutdown of domestic economic activity, which may have disrupted financial transactions, and that outflows accelerated in the second quarter. However, capital flows out of the country hardly seem to have stressed the currency regime. At the same time, changes in foreign-exchange reserves, which could be read as evidence of PBoC market intervention meant to either weaken or strengthen the currency, have also been very modest since 2019.

What if?

While China's currency hasn't been a source of global or regional financial instability during the Covid pandemic, and wasn't during the global financial crisis a decade ago or the Asian crisis a decade before that, it's worth considering more deeply what it might take to genuinely test China's existing preference for currency stability. It is possible that a sufficiently sharp divergence in the three heavyweight currencies in the PBoC's exchange-rate reference basket (USD, JPY, and EUR) might be enough to test current prevailing preferences for CNY stability. Similarly, a sharp enough escalation in trade, diplomatic, or geopolitical tensions with the US might also be a potential candidate.

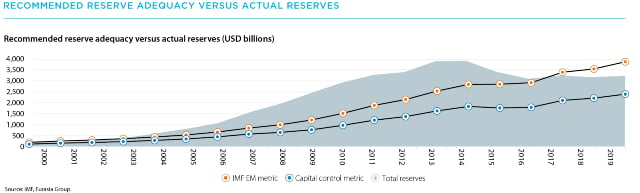

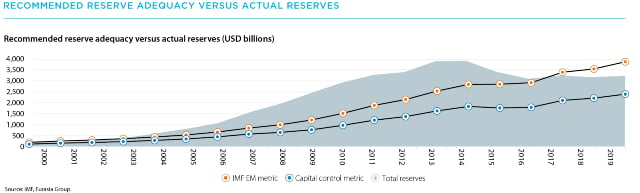

In any of these circumstances, an important issue would be how much control China would have—or even seek—over the CNY. China's reserves of USD 3.2trn are well in excess of short-term external debt of USD 1.2trn, and the central bank has indirect levers of influence over investors to discourage speculative outflows. The PBoC used around a trillion dollars in reserves between 2015 and 2017 defending the currency, but may now be less willing to expend reserves to defend the CNY to the degree it used to. Indeed, in recent years, reserves have been less needed to stabilize the currency.

Moreover, the country's reserves may no longer be the buffer they once were, as under crisis conditions, even a sizeable war chest of reserves can be spent down rapidly. After the substantial outflows of 2015, China's total reserves are now below the IMF's benchmark guidance based on the size of the Chinese economy and banking system if it had an open financial account, although above guidance for governments imposing capital controls. The upshot is that on standard measures, China may no longer have “excess” reserves.

The Bank for International Settlements has stressed that even a current-account surplus or net-creditor position might not be a guarantee of safety, as assets and liabilities are typically in different hands. Liability positions could be concentrated in certain vulnerable sectors, and large foreign asset positions could be subject to stresses in funding or hedging markets.

In recent years, China has relied increasingly on tightening capital controls to prevent excessive CNY depreciation, even as it appears more relaxed about permitting greater movement in the CNY against the dollar. In combination with a credible policy regime, the Chinese authorities' ability to manage the financial account limits the PBoC's reliance on reserves to manage the currency. The PBoC has probably grown more tolerant of exchange-rate volatility because the direct spillovers from CNY rate weakness into domestic credit conditions now appear to be much lower than was the case in 2015.

A weakening CNY would risk significant spillovers to other Asia-Pacific markets

The currency composition of China's debt stock (largely in CNY), the sheer size of its economy and tradeable sector, and the much reduced sensitivity of domestic credit conditions to exchange rate movements mean that currency weakness tightens financial conditions in China far less than in most other emerging markets. A weak CNY that does not tighten Chinese financial conditions would raise the competitive challenges for the rest of Asia. But a weak CNY that does tighten Chinese financial conditions would be a more substantial challenge as it would also likely be associated with weakening Chinese demand.

While outcomes such of these of course are possible, the risk would seem to be low. China's focus on economic growth and providing employment are likely to, as is the case in most countries, be even stronger after the negative labour market impacts of Covid-19. Currency depreciation that encourages destabilizing capital outflows would be counterproductive to such objectives.

Weaker US fundamentals could boost the CNY in relative terms

In the meantime, US economic fundamentals have deteriorated significantly as a result of the Coronavirus crisis. Total US federal debt as proportion of GDP stood at about 108% in the first quarter of 2020, while real GDP contracted by nearly 11% in the first half of this year. Although a rebound is expected in the second half of 2020, it could be several years before the US economy surpasses its earlier level of activity. At the same time, the Federal Reserve's balance sheet has grown considerably, interest rates remain at the lower bound, and both the central bank's asset holdings and the federal debt and deficit will continue to grow rapidly for the foreseeable future. These factors may exert a lasting structural drag on the dollar, which would imply a stronger CNY. To some degree, CNY movements will remain a relative game.

The USD's value erosion, however, shouldn't distract from the CNY's three-peat. For the third crisis in succession the CNY has defied expectations that it might propagate the crisis. Instead, it has retained both the flexibility and ability to move, while also delivering only a modest currency adjustment. China's currency has come of age.

Learn more about Eurasia Group and ANZ's Asia's economy: China's currency at the foundation.

ANZ: IMPORTANT LEGAL INFORMATION

This publication is published by Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited ABN 11 005 357 522 (“ANZBGL”) in Australia. This publication is intended as thought-leadership material. It is not published with the intention of providing any direct or indirect recommendations relating to any financial product, asset class or trading strategy. The information in this publication is not intended to influence any person to make a decision in relation to a financial product or class of financial products. It is general in nature and does not take account of the circumstances of any individual or class of individuals. Nothing in this publication constitutes a recommendation, solicitation or offer by ANZBGL or its branches or subsidiaries (collectively “ANZ”) to you to acquire a product or service, or an offer by ANZ to provide you with other products or services. All information contained in this publication is based on information available at the time of publication. While this publication has been prepared in good faith, no representation, warranty, assurance or undertaking is or will be made, and no responsibility or liability is or will be accepted by ANZ in relation to the accuracy or completeness of this publication or the use of information contained in this publication. ANZ does not provide any financial, investment, legal or taxation advice in connection with this publication.

EURASIA GROUP: IMPORTANT LEGAL INFORMATION

This material was produced by Eurasia Group for use by the recipient. This is intended as general background research and is not intended to constitute advice on any particular commercial investment, trade matter, or issue and should not be relied upon for such purposes. It is not to be made available to any person other than the recipient. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or otherwise, without the prior consent of Eurasia Group.