looking back 25 years later Eurasia Group's

Alexander Kliment and

Willis Sparks look back at the KGB-led

August 1991 coup that failed to save the Soviet Union from Mikhail Gorbachev's attempts to reform it. They also revisit the bizarre role that the Swan Lake ballet played during the chaos of those days.

Sparks recounts what happened and why. Kliment examines what Russians think of that event 25 years later—and how Vladimir Putin can explain it to those who aren't old enough to have experienced it or to have lived under Soviet rule.

Full transcript below.

ALEXANDER KLIMENT: We interrupt this broadcast of Swan Lake to commemorate the 25

th anniversary of the KGB-led coup against Mikhail Gorbachev that hastened the end of the Soviet Union. I'm Alexander Kliment, Russia analyst at Eurasia Group, and I'm joined by my friend, our Global Macro director Willis Sparks.

Willis, at the time of the coup you had just come back from your first trip to the Soviet Union.

WILLIS SPARKS: Yeah, it had been a couple years, but I had friends there and was really, really interested in the story, so I followed it really closely. And I remember coming home and turning on the TV and hearing that Gorbachev was under arrest, which was at the time world-shaking news, as you might imagine. Essentially what had happened was, Gorbachev by that point was a widely discredited figure.

In fact, I'm reminded, in doing some research for this, that there was a joke going on at the time. There was a guy standing in a long bread line in Moscow getting really frustrated. And he says, you know, I'd love to kill Gorbachev. And the guy in front of him in line says, why don't you? And he said, because the line is too long.

So Gorbachev was very unpopular. And in fact, the coup itself, that we're here to talk about today, was as much targeted, in some ways, against Boris Yeltsin, who had already emerged as an important figure, as it was against Gorbachev, because Yeltsin had won an election to become President of the Russian Republic within the Soviet Union, which made him dangerous for Soviet conservatives.

So, at the time, Gorbachev and Yeltsin were involved in a treaty that would have fundamentally changed the Soviet Union and its relationship with the Republics. That alarmed the KGB, who was of course listening on the telephone. The KGB's listening to these plans and decide now is the time to act. Gorbachev and his wife Raisa were in Crimea, of all places, on vacation. And the KGB showed up and put him under house arrest. And they said, you're either going to renounce this treaty that you're talking about or you're going to resign. And Gorbachev said, I refuse to do either of those things. And then the coup was on.

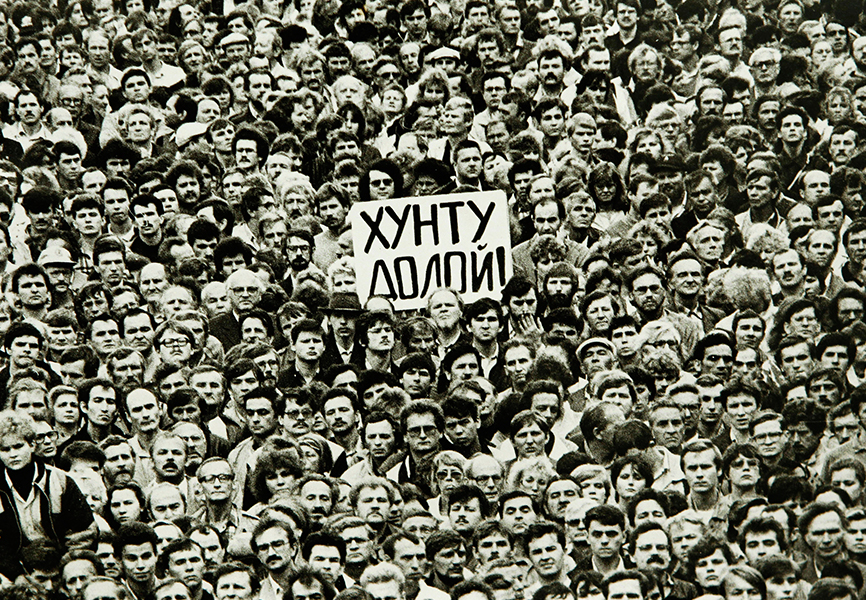

So if you were in Moscow at the time, or anywhere in the Soviet Union, you turned on your TV in the morning on that Monday morning, August 19

th, and there was an emergency committee on, announcing that they were in charge, without much detail. And suddenly, people across Russia watching state-run television are watching Swan Lake for hours and hours, an endless loop of Swan Lake, while the coup moved into motion.

By that evening, the coup plotters held a press conference to explain themselves. And a guy called Gennady Yanayev, who was nominally the leader of this KGB-led coup, he was the vice-president, was visibly drunk on camera and very nervous, saying, Gorbachev is sick, don't worry, we're in charge.

And the thing fell apart from there, because they didn't manage to arrest Boris Yeltsin or any of the two hundred or so people that they planned to arrest. Gorbachev came back to Moscow, and then four and a half months later, the rest is history. The Soviet Union ceased to exist, and Boris Yeltsin became the dominant political figure in the new Russia.

So, this is the point in the conversation where I turn to you and say, speaking of the new Russia, here we are 25 years later. What do we know about how people in today's Russia remember that coup 25 years ago and its impact on the fall of the Soviet Union? What do they remember and what do they think about it?

KLIMENT: Yeah, I mean, views on the coup in Russia have always been very divided, right? It's one of these questions, you know – tell me what you think of the coup and I'll tell you who you are – this type of thing in Russia. There are people who, in hindsight, view the coup as a noble if flawed attempt to rescue Russia from the political and economic and geopolitical chaos that would follow the Soviet collapse. And there are people who see the coup as the last gasp of an oppressive and broken system that deserved to die.

What's most interesting, now, is that for the first time since 1991, 50 percent of Russians now say that they no longer remember the coup or don't know what happened. And that kind of vacuum of historical memory, I think, is significant in a country where 90 percent of the population say they get their news primarily from state-dominated media and state-dominated television.

SPARKS: You've got a whole generation of Russians now that are just not old enough to remember this stuff.

KLIMENT: Exactly. So that's significant. And, you know, it's significant because it gives the state tremendous power to shape how Russians view their recent history, how Russians view the Soviet collapse.

SPARKS: So speaking of the state, I'm asking what Russians are thinking and saying about it. Let's talk about President Putin now. Because one of the ironies of the coup is that, whatever he thinks about the events 25 years ago, at a time when he was serving in the KGB and resigned, apparently, during the coup, the emergence of Yeltsin created, as we know, the emergence of Putin. Yeltsin named Putin as his designated successor. Here we are 25 years later. So as the Russian government commemorates the events of 25 years ago – the coup but mainly the dissolution of the Soviet Union – how does President Putin explain this to Russian people in a way that is consistent with his current political goals?

KLIMENT: Well, Putin owes a lot to the collapse of the Soviet Union in the sense that it was a catapult that put him on a track to ultimately becoming President of Russia. He's also spoken, you know, in terms of, he's spoken about the Soviet collapse in negative terms as well. He once said it was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the twentieth century.

I think the kind of things that Putin will focus on will be, look, that the intention of the coup was to preserve order and to rescue Russia's sovereignty. And order and sovereignty have been two major points of Putin's narrative about Russia, particularly in his most recent term as President. He's always cast himself as a person who is pulling Russia up off of her knees, kind of rescuing Russia from the humiliations of the 1990's. And I think we can expect a lot of that narrative to come through in how the state frames not only the coup anniversary, but also the anniversary of the Soviet collapse.

And next year, of course, will be the 100

th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, which will come on the eve of Russia's next presidential election. So there's a sort of rich historical stew for the Kremlin to draw on over the next year.

SPARKS: But Putin, over the course of this fall, can talk about this as a cautionary tale of what happens when the state is not in control and law and order is very much at risk.

KLIMENT: Yeah, I mean Putin once wrote that the greatest threat to a government is paralysis of the state. And I think that was one of the big lessons that he drew from the Soviet collapse, was that the system may have been bad, but that the biggest problem was that the state itself became paralyzed. In a lot of ways, Putin has dedicated his entire political life in Russia, among other things, to preventing the Russian state from becoming paralyzed or weakened the way that it did after the Soviet collapse.

SPARKS: And paralysis of the state is the great legacy of this coup from 25 years ago.

This is Alexander Kliment, I'm Willis Sparks. We now return you to Swan Lake.